2. Disaster Mitigation

It is estimated that more than half of the hospitals in Latin

America and the Caribbean are located in disaster-prone areas,

which makes them unsafe. This situation is not specific to this

Region; the tsunami and earthquakes in India (Gujarat), Iran (Bam),

and Pakistan also severely affected health infrastructure. Building

codes for health facilities should not only ensure the survival

of staff and patients but also be stringent enough to permit facilities

to continue functioning.

The destruction of Mexico’s Hospital Juarez in 1985, which

resulted in the death of 561 patients and staff, prompted the

Region to launch a massive awareness campaign to increase the

structural and nonstructural safety of health facilities. This

concern, at first a regional issue, evolved into a global priority

in January 2005, when the “Hyogo Framework of Action for

2005-2015,” the global blueprint stemming from the Second

World Conference on Disaster Reduction held in Kobe, Japan, included

a specific indicator on vulnerability reduction in the health

sector.

When PAHO/WHO speaks about disaster mitigation it focuses on

how the health sector can reduce the physical and functional vulnerability

of all types and levels of health facilities. At the regional

and national level, PAHO advocates for and collaborates with Ministries

of Health and Planning, financial lending institutions, professional

associations and others to establish regulatory agreements that

contribute to making hospitals safe in disaster situations.

Safe Hospitals

The

goal of “hospitals safe from disaster,” which was

approved by 168 countries worldwide at the 2005 Kobe Conference,

complements PAHO/WHO’s commitment to the importance of building

new hospitals with a level of protection that guarantees they

can remain operational after a disaster. This commitment also

extends to applying risk-reduction mitigation measures in existing

facilities to reduce their

The

goal of “hospitals safe from disaster,” which was

approved by 168 countries worldwide at the 2005 Kobe Conference,

complements PAHO/WHO’s commitment to the importance of building

new hospitals with a level of protection that guarantees they

can remain operational after a disaster. This commitment also

extends to applying risk-reduction mitigation measures in existing

facilities to reduce their

vulnerability. To assist in making strides in this field, PAHO

advocates for and collaborates with national authorities in the

Region to develop tools, policies and regulatory agreements as

well as to provide training for engineers, building inspectors

and project managers.

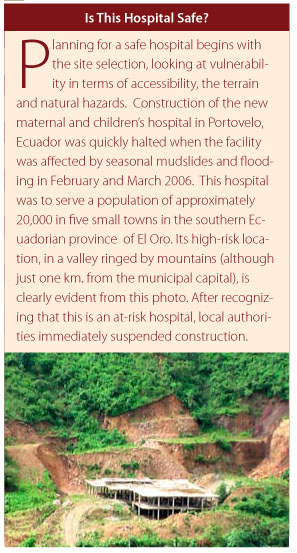

One of the most important advances in 2006 was the development

of a Hospital Safety Index, a tool or scorecard that measures

and ranks a health facility’s level of safety in the context

of its geographical location and exposure to natural hazards.

As not all hospitals face the same risks, nor are they built using

the same standards, this model incorporates a wide range of factors

that measure safety. To reach a final safety score, hospitals

must look at factors such as where the hospital is built (i.e.,

is it in an earthquake-prone area?), the structure of the building,

its configuration, construction materials used, and its previous

exposure to hazards. Attention is also given to non-structural

hospital components such as the electric system, water supply

and reservoir, ventilation, furniture, medical equipment, etc.

The final section of the Hospital Safety Index evaluates the organization

of the facility, the existence and application of an emergency

plan and the level of awareness of staff. The DiMAG, the Disaster

Mitigation Advisory Group, prepared the first draft of this scorecard,

which can be used by engineers, hospital directors and disaster

managers and takes very little time to apply. However it does

not replace an in-depth vulnerability assessment conducted by

experienced engineers. And, having a tool to assess safety, with

a focus on critical services, does not automatically mean that

recommended measures will be taken to improve the situation. The

Hospital Safety Index form is attached in Annex

8.

Mexico

and, to a more limited degree St. Vincent, Dominica Cuba, Peru

and Costa Rica, conducted pilot surveys to test the Hospital Safety

Index. The application of the Safety Index in Mexico, a large

country with more than 3,000 public and private hospitals, offered

an interesting example of how this process works. In 2006, Mexico

created a National Committee for the Diagnosis and Certi fication

of Safe Hospitals, made up of representatives of a variety of

institutions such as the Mexican Hospital Association, the Social

Security Institute and the Secretary of Health, among others.

The Committee helped to pilot the application of the Hospital

Safety Index in more than 100 Mexican health facilities which

were determined to be at risk, either because of their geographic

location or due to their critical place in the health network.

Mexico

and, to a more limited degree St. Vincent, Dominica Cuba, Peru

and Costa Rica, conducted pilot surveys to test the Hospital Safety

Index. The application of the Safety Index in Mexico, a large

country with more than 3,000 public and private hospitals, offered

an interesting example of how this process works. In 2006, Mexico

created a National Committee for the Diagnosis and Certi fication

of Safe Hospitals, made up of representatives of a variety of

institutions such as the Mexican Hospital Association, the Social

Security Institute and the Secretary of Health, among others.

The Committee helped to pilot the application of the Hospital

Safety Index in more than 100 Mexican health facilities which

were determined to be at risk, either because of their geographic

location or due to their critical place in the health network.

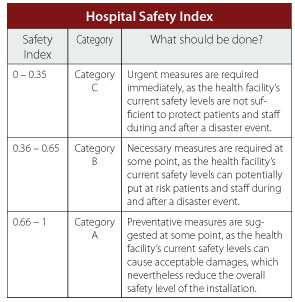

As

a first step, more than 60 professionals were trained to use this

tool, which classifies the level of safety in hospitals into categories

A, B or C (see box). The Index was then applied in 104 health

facilities by the end of November 2006. The results showed that

more than 60% of these hospitals were classified as safe in terms

of structural and non-structural components. However, almost the

same percentage were deemed to require improvement in the functional

component (disaster planning, organization, training, critical

resources, etc.) After reviewing the results, Mexico’s coordinator

of the Civil Protection system committed to include “Safe

Hospitals” as a national disaster reduction priority, for

which he received the backing of the country’s newly-elected

president. Mexico is committed to applying the hospital safety

index to all high-risk facilities (slightly over 1,000) in 2007

and to begin the process of certifying those facilities with an

“A” rating. The results of this pilot project are

attached in a presentation in Annex 9.

As

a first step, more than 60 professionals were trained to use this

tool, which classifies the level of safety in hospitals into categories

A, B or C (see box). The Index was then applied in 104 health

facilities by the end of November 2006. The results showed that

more than 60% of these hospitals were classified as safe in terms

of structural and non-structural components. However, almost the

same percentage were deemed to require improvement in the functional

component (disaster planning, organization, training, critical

resources, etc.) After reviewing the results, Mexico’s coordinator

of the Civil Protection system committed to include “Safe

Hospitals” as a national disaster reduction priority, for

which he received the backing of the country’s newly-elected

president. Mexico is committed to applying the hospital safety

index to all high-risk facilities (slightly over 1,000) in 2007

and to begin the process of certifying those facilities with an

“A” rating. The results of this pilot project are

attached in a presentation in Annex 9.

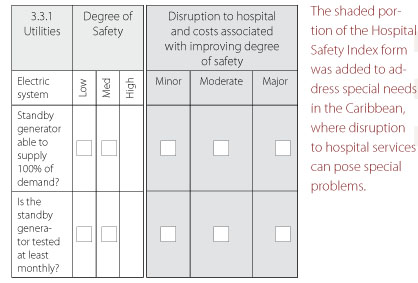

In the Caribbean—where a single hospital can be of vital

importance, as it may be the only one in a country—additional

considerations have been added to the form to measure the degree

of disruption to a health facility if the recommendations are

implemented and the cost associated with doing so. Authorities

can appreciate at a glance that with limited funds and minor disruption,

their safety score can be improved. The box below, shows a sample

of this expanded form.

Most countries in which the Hospital Safety Index was piloted

were very cooperative and enthusiastic about applying it. However,

for understandable reasons, health authorities or ministries of

health requested that the results be kept confidential!

Countries Take Steps to Protect their

Health Facilities

In Costa Rica,

the impact of the 2005 fire that destroyed part of the Calderon

Guardia Hospital in Costa Rica, killing 19 patients and staff,

was not only measured in economic terms but also in the social

and political repercussions it left in its wake. The painful realization

of the vulnerability of health care facilities to manmade as well

as natural disasters prompted the directors of Costa Rica’s

Social Security System (CCSS), which is responsible for and the

only provider of the nation’s hospital services, to prepare

a policy to safeguard the country’s health services. PAHO/WHO

supported the government and a multidisciplinary team, which they

created to develop this policy. The result was a proposal for

an institutional policy on Hospital Safety that identified the

steps necessary to transform a policy “on paper” into

a reality.

In order to create a national committee to develop a safe hospital

policy, the CCSS had to formally modify its organizational structure.

The policy which was created focused on investments in new facilities,

existing facilities and on preparedness actions to protect the

lives of patients and staff. A number of intersectorial measures

were put in place to monitor compliance with this policy. Technical

reference material on a model national program for safe hospitals,

which PAHO/WHO helped to develop during earlier efforts with other

countries in the Region, was used in Costa Rica.

Costa Rica’s safe hospital policy set forth deadlines,

allotted funds for activities and assigned responsibilities. Once

this work was completed, the policy was presented to the board

of directors of the CCSS, which approved it through a formal resolution.

To begin implementation of the policy in Costa Rica’s health

facilities, the CCSS assigned US$3 million of its own funds. More

concretely, in the design of the new Heredia Hospital, vulnerability

reduction measures were included; particularly noteworthy were

measures designed for fire safety, a tangible legacy of the tragic

Calderon Guardia fire.

Paraguay’s

Ministry of Public Heath and Social Welfare also demonstrated

a commitment to protecting the country’s health facilities.

The Minister of Health, in a letter to PAHO/WHO, requested assistance

in assuming responsibility for carrying out a Safe Hospitals program

to complement parallel activities aimed at achieving the Millennium

Development Goals. It is important to note that the political

support from a country’s highest level health official is

key to the success of efforts in this field. Specifically, the

Ministry sought help in the form of technical experts to carry

out an evaluation of the vulnerability of the Ministry’s

health facilities to disasters, to arm the country with the information

necessary to develop projects and strategies within the framework

of Safe Hospitals.

In Argentina,

the Ministry of Health, with the support of PAHO, organized a

250-person meeting on Safe Hospitals for the Province of Buenos

Aires. The meeting was held to raise awareness among hospital

directors, maintenance supervisors, municipal health leaders and

deans of faculties of medicine, engineering and architecture of

the importance of reducing vulnerability in health facilities.

The Ministry of Health proposed several lines of action for safeguarding

provincial hospitals, including passing a legal framework to regulate

the construction of new health facilities, conducting vulnerability

assessments in existing structures, promoting specialized training

in architecture and engineering and earmarking 30% of the Ministry’s

annual budget for infrastructure for maintenance and safety of

hospitals.

Protecting Health Facilities: Who is

in charge?

There is a general agreement that in order to protect health

facilities and reach the goal of safe hospitals, key actors outside

the health sector must be involved. Unfortunately, this premise

is still not clear in many countries. Peru went through a sometimes

complex and challenging process at the national decision making

level to answer the basic question: who is in charge of protecting

health facilities?

The Peruvian Civil Defense Institute, as part of its routine

activities in public and private facilities, decided to conduct

a safety inspection of the main hospital in Cajamarca, a city

in northern Peru. The results of the evaluation showed that the

hospital indeed required significant improvements in areas that

were outlined in the safety norms of the national Civil Defense.

While the issues arising from the findings of the evaluation were

resolved, the hospital might have to be closed. This internal

report was leaked to the media by local authorities, and quickly

the Minister of Health denied the Civil Defense the right to inspect

hospitals; the Minister went further and asked for the resignation

of the head of the Civil Defense because of interference in the

health sector. There was concern that if inspections were performed

in other hospitals, the results might be similar and this would

have an adverse political and social impact.

PAHO/WHO helped both institutions to resolve this impasse, recognizing

the authority of the Civil Defense to evaluate all public and

private facilities, but at the same time, indicating that hospitals

cannot be evaluated in the same way as schools, shopping centers,

restaurants or other public places. The Ministry of Health and

the Civil Defense agreed to work together, with the technical

support of PAHO, to prepare technical guidelines to assess hospital

safety, to train safety inspectors in health facilities and to

identify and improve the safety of health facilities that are

found to be unsafe according to the new guidelines.

Reaching common ground proved to be in the best interest of

the Peru’s public and private facilities. The Civil Defense

offered to finance the evaluation of the first two hospitals,

using public disaster mitigation funds. The new guidelines for

hospital safety assessment, prepared with the support of the Peru-Japan

Center for Earthquake Engineering Research and Disaster Mitigation,

were officially approved by the Government of Peru, becoming the

first national norm of its kind in the Americas. Peru is now training

and accrediting hospital safety inspectors and will soon begin

the assessment of public and private health facilities countrywide.

Advocacy and Awareness

By the end of 2006, it had been decided that the focus of the

2008-09 World Disaster Reduction Campaign of the International

Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) would be on reducing the

risks of natural hazards on the health of people worldwide. This

decision provided an excellent opportunity for PAHO/WHO to use

this global forum as a platform to further promote a risk reduction

and mitigation strategy in this Region, under the banner of Safe

Hospitals. Because of the Organization’s substantial experience

and achievements in this field, the ISDR has reached out to PAHO/WHO

for technical and advocacy support as the campaign develops. Although

work will begin in earnest in 2007, PAHO/WHO proposes that global

focus be on ensuring the structural resilience of health facilities

to protect the lives of the patients and staff, the functional

continuity of hospitals and key health services in the aftermath

of disasters, when they are most needed. The campaign will provide

an excellent chance to engage the public and decision makers in

all sectors as stakeholders in the safety of their country’s

hospitals.

A new DVD program on Safe Hospitals

has been prepared to raise awareness and promote the concept and

strategy, with a perspective that extends beyond the health sector.

The video explains what a safe hospital is and why we must safeguard

these critical facilities. It highlights examples of good practices

in the Region, destroying the myth that it would be too expensive

or even impossible to build hospitals with safeguards to ensure

they continue to function after disasters. The DVD combines video

footage and interviews with important decision makers in several

countries in the Americas who share positive experiences and lobby

for safe hospitals. The program is geared toward the political

arena to raise awareness at the decision- making level during

planning or execution of hospital construction or improvements.

However, it is equally as suitable for use in disaster mitigation

training activities. In addition to serving as an excellent reference

source, this type of program will become key to PAHO’s advocacy

efforts in conjunction with the ISDR global campaign and offer

an example to other regions of the world wishing to create similar

products.