3. Disaster Response

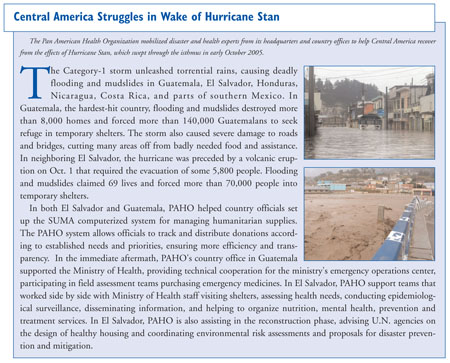

Several major natural disasters struck the Region in 2005, including widespread floods in Guyana, an earthquake in Colombia, and the most devastating of all, Tropical Storm Stan, which lingered over Guatemala and El Salvador, producing mudslides and killing several thousand people. Disasters outside the Region also had an impact on our annual workplan, as PAHO/WHO staff supported relief efforts related to the tsunami in south Asia, hurricane Katrina in the U.S. and the massive earthquake centered in the Kashmiri border area between India and Pakistan.

NATURAL DISASTERS

In Latin America and the Caribbean

Many large-scale natural disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean do not make the front pages of the newspapers, even though their impact strains the resources of the affected country. In most cases the events are handled locally and the health sector requires only limited external support. This was the case with a number of disasters in South America in 2005: earthquake in Tarapacá, Chile (June); earthquakes in Peru (September and October); floods in Venezuela (Nov.), Colombia (September and November), Bolivia (March, September and November); drought in Paraguay, Bolivia and Ecuador. Other natural phenomena were also an issue: storms in Uruguay (August); extreme cold wave in Peru (June) and Bolivia (April); fires in health care facilities in Argentina (July), social conflicts in Bolivia (May, June); volcanic eruptions in Ecuador and Colombia; and airplane crashes in Venezuela and Peru (August). The fact that some Ministries of Health were self-sufficient in their response to these natural disasters illustrates that countries—and particularly the national disaster offices in the Ministries of Health—have improved their disaster preparedness and response capacity.

Outside the Americas

In 2005, solidarity with other WHO Regions offered opportunities for PAHO to help respond to large-scale needs in countries where we do not normally work. The repercussions from the 26 December 2004 tsunami that affected 11 countries in Asia lasted well into 2005. Indeed, the management of the post-tsunami response is still a principal area of work for WHO and its Southeast Asia Regional Office (SEARO), whose human resources were severely overstretched by this crisis. PAHO assisted WHO by providing staff to supplement SEARO’s emergency response coordination in Banda Aceh, Indonesia (two months as health cluster lead) and in New Delhi (information and project management).

The Logistics Support System (LSS) was used for the first time in Banda Aceh to assist the Ministry of Health with the huge influx of drugs and medical supply donations. However, a lesson was learned from this first deployment. Because the LSS system was neither requested nor set up early on (understandable given the magnitude of this disaster), it was not adopted as readily as it has been in other situations, as people were reluctant to change from the Excel spreadsheets or manually-entered data forms they were already using.

In August and September 2005, the United States was seriously affected by a number of hurricanes, the most notable of which was Hurricane Katrina. For the first time, practical collaboration was established between the UN system and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). PAHO/WHO formed part of the Hurricane Katrina Emergency Operations Center which was set up in suburban Washington D.C. (Arlington, VA). Also, unprecedented was the participation of health disaster experts from PAHO and from other countries in the Americas. In support of these efforts, PAHO experts participated in rapid needs assessments in Texas, Mississippi and New Orleans; evaluated shelter management; and carried out water and sanitation and hospital assessments.

WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Office (EMRO) asked PAHO to assist in deploying various experts to the earthquake-affected areas in Pakistan, Kashmir and the northwest frontier province. As was the case in Banda Aceh, a PAHO/WHO staff member served as coordinator of the health cluster in Islamabad for several months. The Organization also helped to identify and deploy experts in LSS, epidemiologists and engineers with experience in assessing structural damage caused by earthquakes and identifying appropriate mitigation measures. For the first time, all WHO field offices in Kashmir adopted the LSS and more than 15 persons from the Ministry of Health were trained to use it. The UN Joint Logistics Center, with support and encouragement from DFID, has begun to use LSS/SUMA to compile data on incoming relief goods in order to identify gaps and produce reports for donors.

Latin America and the Caribbean have accumulated a substantial body of experience in certain specialized areas of disaster reduction, particularly mitigating the impact of natural disasters and the application of construction standards for hospitals. The experience was helpful in the aftermath of major disasters in other regions of the world. However, “exporting” disaster managers and other experts (whether PAHO staff or nationals from PAHO/WHO Member States) to other regions also benefits PAHO/WHO for a number of reasons. First, lessons learned elsewhere can be incorporated into policy and strategy in the Americas; second, it helps to identify gaps in knowledge in this Region (the need for logistics procedures and experienced staff; the importance of a trained disaster response teams on standby and the impact of a well established DEWS (disease early warning system) were immediately included into PAHO activities); and lastly, it allowed us to work directly with staff from other regional health (non-disaster) agencies with whom we have little interaction (Health Canada is an example.) Following the tsunami in southeast Asia, experts from Sumatra, Indonesia and Thailand came to work in the Caribbean (which is potentially at-risk of tsunamis) and were able to share their experience, including the difficulties encountered in managing and especially identifying dead bodies.

SOCIAL CRISES

Haiti

Haiti is in a constant state of social crisis, which is exacerbated when natural or manmade disasters strike. Although many Caribbean countries are exposed to the same natural hazards, the devastation and loss of life and livelihoods they experience do not compare to the impact on Haiti. Physical, social, economic and environmental conditions in Haiti make it one of the most vulnerable countries in the world.

Although on several occasions Haiti was in the direct path of a tropical storm and/or hurricane, in 2005 the country was largely spared (as compared to 2004). However, flooding led to landslides that destroyed crops and left thousands homeless and affected. This compounded an already-worsening social crisis that has been deteriorating for several years. Kidnappings and other serious crimes increased in 2005 to previously unforeseen rates and the unstable security situation directly affected PAHO’s activities. The example of PROMESS, whose operations were severely compromised, points to the need to maintain flexibility and seek solutions.

In 2005, CIDA funded a special project to reduce the vulnerability of the population of Haiti to natural disasters such as floods, landslides and hurricanes. A special advisor was recruited in July and based in Port-au-Prince to:

- Strengthen health disaster management at the departmental level in three provinces.

- Strengthen disaster preparedness capacity in one particularly vulnerable community of each province.

- Improve national response mechanisms in supporting two departments and disaster response authorities at central and departmental level.

Colombia

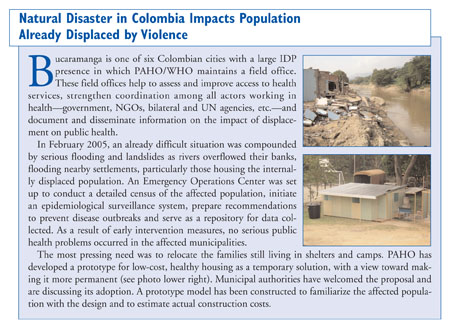

For several years, PAHO/WHO has managed a project to improve the health situation of those affected by violence in Colombia and neighboring countries, creating field offices throughout Colombia to document and disseminate health information on refugees and the internally displaced population (IDPs) as well as the impact on receptor communities. These officesalso strengthen coordination and leadership within the health sector at all levels by improving the response capacity and advocating for increased access to health services. Collaborative activities with many different actors—local government, NGOs and public sector international organizations—promote the transfer of information and knowledge sharing and increase long-term sustainability.

PAHO/WHO is working to improve health statistics on IDPs. Highlights from the work of the field offices include:

- The Cali office is testing tracking software that will speed up the allocation of national IDP health funding, enable real-time planning and enhance emergency response capacity, while also providing detailed health information on IDPs.

- The Bucaramanga field office organized a technical workshop on design proposals for healthy IDP housing. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is now using the PAHO healthy housing design in 150 IDP homes in Santander.

- The newly-trained Valle del Cauca indigenous health brigades are now fully functional. The Cali office is expanding this training to include a response plan for complex emergency situations in protected indigenous areas.

In recent years, the IDP problem has extended beyond Colombia, as refugees spill across the borders of neighboring countries, and currently activities are also taking place in Ecuador, where refugees are gaining additional rights to health services, as information is gathered both about their needs and the impact on the health of the receptor-communities. The response capacity is improving along the border, as is cross-border cooperation on IDP/refugee issues. Activities in Panama remain suspended, but the new office in Northern Santander is expected to increase cross-border activities in Venezuela.

POST-DISASTER ASSESSMENTS IN HEALTH

PAHO/WHO Regional Disaster Response Team

Many countries in the Americas have the capacity to handle emergency situations on their own. Yet on occasions, an event will occur of such magnitude that it overwhelms the response capacity of a country and external assistance is required. Bilateral or UN response teams (Cuba, Venezuela, Argentina and others) have responded on many occasions. However, a regional response mechanism, consisting of experts from PAHO and Member States, previously selected for their experience, seems to be the most feasible approach.

In 2005, efforts stepped up to formally consolidate this regional disaster response team (a Caribbean-only team had been in place for more than 20 years). Preliminary efforts included the development of guidelines and adjustments to internal PAHO/WHO administrative procedures to allow greater flexibility and speed in the response. By the end of 2005, the regional response team include some 40 persons with a variety of skill sets—project management, general administration, disease surveillance, water and sanitation, structural engineering and others—from English, French and Spanish-speaking countries.

Logistics Support System

It has been two years since work began in earnest to develop and program the software for the LSS system (Logistics Support System8). The LSS is a jointly-owned tool, available to all humanitarian institutions. It is designed to improve coordination, develop the local capacity to manage logistics in emergency situations, improve accountability and transparency and reduce duplication of efforts.

8. The LSS is a joint initiative of six UN agencies (WHO, WFP, OCHA, UNICEF, UNHCR, and PAHO) to consolidate the experiences of the UN Joint Logistics Centre (UNJLC) and the SUMA system in the Americas with regard to the management of humanitarian supplies. LSS combines the strengths of these two successful initiatives that have operated in different environments and have served complementary purposes. The work carried out during 2005 was extensive, as were the results. Activities focused on testing the release of the software, which was delivered from the contractor at the end of 2004, preparing specifications for revisions and improvements, developing a practical manual in English and Spanish (still in draft version) and a website exclusively for LSS. Other activities included carrying out LSS training courses in Panama City and the Maldives and overseeing the first deployment of the LSS following Hurricane Stan in Guatemala and El Salvador and, globally, in Pakistan to respond to the South Asia earthquake. Highlights of the achievements in 2005 include:

Achievement

Date

Receipt of first final version from vendor, including documentation, etc.

January 2005

Test of first final version.

February-March 2005

First final version workshop with vendor to agree in needed changes/improvements.

April 2005

Second final version received from vendor.

July 2005

LSS group accepts June 2005 version as final release and vendor agrees to provide service for errors through the purchased warranty.

July 2005

First LSS training course held in Panama, City, Panama.

August 2005

LSS implemented in Guatemala and El Salvador following Hurricane Stan.

October 2005

LSS implemented in Kashmir Region following earthquake.

October 2005

LSS training course held in Maldives.

November-December 2005

PAHO/WHO will continue supporting SUMA, which was developed by and for Latin American and Caribbean authorities/institutions. The expertise, level of personnel trained and experiences gained in SUMA are assets that are making the transition to LSS easier in the Americas. As a stand-alone logistic support system, SUMA will be enhanced by the introduction of the new software.

The initial training sessions and deployment of the LSS, revealed several lessons:

- Although the LSS has greater capabilities than SUMA, it also requires better trained human resources and more sophisticated equipment.

- The use of the web-based application can be cumbersome if good connectivity is not available.

- As we learned with SUMA, political sensitivities still affect how transparently data can be published on the Internet.

- In any new software “bugs” become apparent during the installation and the first days of operation; an expert in LSS with good IT experience should accompany field deployments for the foreseeable future.

Return to index

Next section